It’s All Smoke and Mirrors

Facts and falsehoods about the health concerns of vaping

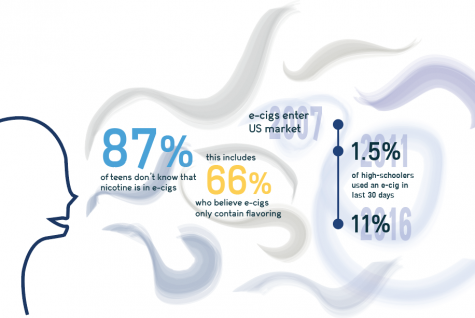

You know a product is a big deal when it has its own verb. Juuling, or the use of Juul-brand e-cigarettes, is a perfect example, having caught the attention of Palo Alto High School administrators and students alike. At the same time, teen use of e-cigarettes is on the rise nationwide: according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, about 11 percent of high schoolers reported using an e-cigarette in the last 30 days during a 2016 study. That figure was 1.5 percent in 2011.

While a wide variety of e-cigarette brands exist, Juul is generally recognized the most popular at Paly — and it shows. School janitor Albert Hidalgo, who monitors the bathrooms in the Media Arts Center, says he finds three to seven discarded Juul pods on any given day.

“If I were to go substitute for one of my coworkers, I’d find them in their restrooms as well,” Hidalgo says. “It’s everywhere.”

But while everyone and their mother recognizes the sleek, rectangular outline of a Juul, not all students understand its health risks. How addictive are e-cigarettes? Do flavorings in e-liquid pose a major health risk? Is second-hand exposure to Juul vapor harmful?

Unfortunately enough, the answers to these questions are not clear. E-cigarettes entered the American market in 2007, and there are many things we don’t know about their effects on the human body.

What we do know is that e-cigarettes contain the addictive chemical nicotine, a fact unknown to the majority of teens. According to a study by the National Institute of Drug Abuse, 66.0 percent of teens believe e-cigarettes contain only flavoring, while 13.7 percent do not claim to know what is in their e-cig, possibly because manufacturers are not required to list ingredients.

Nicotine’s effects on a teenager’s developing brain are well-established. So while current evidence suggests that e-cigs are safer than traditional cigarettes, or “combustibles,” students should be aware that by using them, they are still using an poorly regulated, addictive substance with potential consequences on health.

“It [nicotine] is like a key that comes to the lock and … releases a number of different neurochemicals.”

— Judith Prochaska, Stanford associate professor

To more clearly understand the process of addiction, we spoke to Associate Professor Judith Prochaska, a Stanford researcher specializing in tobacco and e-cigarette use and marketing. The human brain, Prochaska says, contains nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. These receptors detect nicotine molecules in the brain and then bind to them.

“It [nicotine] is like a key that comes to the lock and … releases a number of different neurochemicals,” Prochaska says.

These chemicals, such as dopamine, norepinephrine and GABA (gamma-Aminobutyric acid), result in feelings of euphoria, relaxation and increased focus. However, problems arise when the brain becomes overly reliant on them.

“Your brain changes as a result of that nicotine exposure,” Prochaska says. “You actually upregulate [increase the amount of] nicotinic receptors that then become hungry for the drug when you don’t have it.”

While it’s true that the upregulation process eventually reverts itself, this process is slow and doesn’t completely repair the damage. According to Prochaska, a former smoker can feel tobacco cravings even years after kicking the habit.

How could such a small drug have such a powerful effect? The answer lies in the absorption of nicotine in the lungs. According to Prochaska, a single lung has the surface area of a tennis court, allowing the lungs to receive and pass nicotine into the brain more quickly than other methods, resulting in a greater chance of addiction.

For a Paly student taking a puff of a Juul in a school bathroom, the dangers of combustibles may seem miles away. This thinking isn’t entirely unfounded: After all, e-cigarettes generally contain less nicotine and fewer toxicants than combustible cigarettes. In 2013, an international research team found that certain compounds, namely carbonyls, volatile organic compounds, nitrosamines and heavy metals, appeared in e-cigs with concentrations that were 9-450 times lower than in combustible cigarettes.

“There are so many aspects of using a cigarette that contribute to addiction,” says Michael Siegel of Boston University. “And while the Juul is able to simulate a little bit of that, it’s still a very different type of behavior.”

“They [e-cigs] are a better alternative to what I’ve been doing before.”

— Adrian, anonymous Paly student and former smoker

Siegel, a tobacco expert fighting to curb cigarette use, contends that e-cigarettes are a safer alternative. He even encourages smokers to use them as a quitting aid, a method that has aided people like Adrian. Adrian, a Paly student whose name has been changed to maintain anonymity. acknowledges that e-cigs are “the lesser of two evils” compared to combustibles, and no longer uses either as of several weeks ago.

“The number [of toxins] is low enough that it wouldn’t cause anything in the near future,” Adrian says. “All I know is they’re a better alternative to what I’ve been doing before.”

While some tout vaping’s potential benefit to society, others have seen evidence to the contrary.

“I’ve worked with a lot of smokers who say ‘This doesn’t do it for me,’” Prochaska says. “‘I miss the real thing.’”

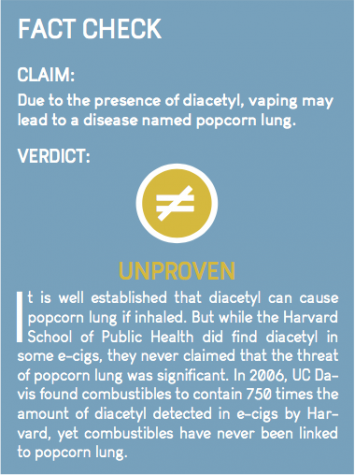

Putting aside the smoking debate, Siegel believes that misconceptions about vaping are common. For example, a 2015 study identified a chemical called diacetyl in flavored e-liquids. While diacetyl causes lung disease in high concentrations, Siegel points out that combustible cigarettes also contain the chemical, but have never been linked to the disease.

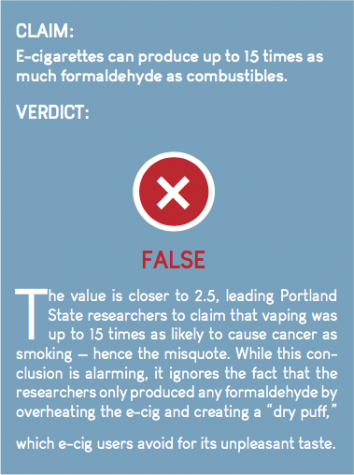

Siegel also dismisses complaints about the presence of a carcinogen (cancer-causing substance) named formaldehyde. The finding comes from a recent study stating that vapers could be exposed to 2.5 times as much formaldehyde as regular smokers. However, a letter of response (which Siegel co-authored) pointed out that these levels of formaldehyde only occured during a “dry puff,” causing a nasty taste which e-cig users are careful to avoid. Others criticized the study’s use of only one e-cigarette brand. A follow-up study which tested five commercial e-cigarettes found that three of them actually produce less formaldehyde than combustibles under normal conditions. Experts still aren’t sure whether vaping affects the adolescent brain. Prochaska errs on the side of caution.

Siegel also dismisses complaints about the presence of a carcinogen (cancer-causing substance) named formaldehyde. The finding comes from a recent study stating that vapers could be exposed to 2.5 times as much formaldehyde as regular smokers. However, a letter of response (which Siegel co-authored) pointed out that these levels of formaldehyde only occured during a “dry puff,” causing a nasty taste which e-cig users are careful to avoid. Others criticized the study’s use of only one e-cigarette brand. A follow-up study which tested five commercial e-cigarettes found that three of them actually produce less formaldehyde than combustibles under normal conditions. Experts still aren’t sure whether vaping affects the adolescent brain. Prochaska errs on the side of caution.

“We know that the frontal lobe — the decision-making, impulsive, control part of the brain — is still developing out to age 25,” Prochaska says. “You want to protect it from things that are going to change it.”

Siegel, on the other hand, maintains that no significant risk of brain damage has been found.

“Let’s say that … it’s true that nicotine is impairing adolescent development,” Siegel says. “You wouldn’t know it. The only way to detect it would be to have them [teens] … do sophisticated neuropsychological behavioral testing.”

But e-cigs are the uncharted territory of health research, with Juuls being the most powerful of the bunch, using a nicotine salt that quickly absorbs in the bloodstream. Perhaps caution is the best policy, which Siegel agrees with.

“There are no positive effects of vaping,” Siegel says. “It’s important that we try to discourage youth from vaping at the same time as we try to encourage adults who are already smokers to switch to vaping if they’re not able to quit completely.”

“We still don’t know a lot … so it’s hard to say ‘this is what you should do,’” Prochaska says. “I would say don’t use an e-cig with nicotine in it. But I can’t guarantee that one that says it doesn’t have nicotine isn’t going to have nicotine, because it [the industry] isn’t well-regulated.”

“It’s important that we try to discourage youth from vaping … as we try to encourage adults who are already smoking to switch to vaping.”

— Michael Siegel, Boston University professor

Not everyone who vapes uses Juul e-cigs, and not all of them vape recreationally. But for the undoubtable majority who do both, there is good news and bad news. The good news is that e-cigarettes do not appear to pose the same risks as their traditional counterparts. The bad news is threefold. First, a safer version of a harmful product is still harmful. Second, because the vaping industry is fairly unregulated, companies are free to misrepresent their products and what they contain. And third, because there is a lack of scientific information on e-cigarettes, new dangers associated with vaping may eventually come to light.

“We don’t know the long term effects because it [e-cigarettes] are such a new product,” Prochaska says. “It took decades before people appreciated the harms of combustible cigarettes.”

While demonizing e-cigs is counterproductive, those who use them ought to consider the risks to make informed decisions about their health.