Bilingualism on the Brain

The effects of multilingual life

PARLEZ-VOUS FRANÇAIS? Juniors Grace Lam (left) and Saki Matsumoto (right) converse in French. Both students are bilingual and learning a third language. Lam grew up speaking Mandarin and Matsumoto speaks Japanese. They are now developing their linguistic skills in Advanced Placement French. “I think that it [knowing Mandarin] has given me a better ability to pick up other languages,” Lam says.

Walking around Palo Alto High School campus, it’s not rare to hear conversations in foreign languages.

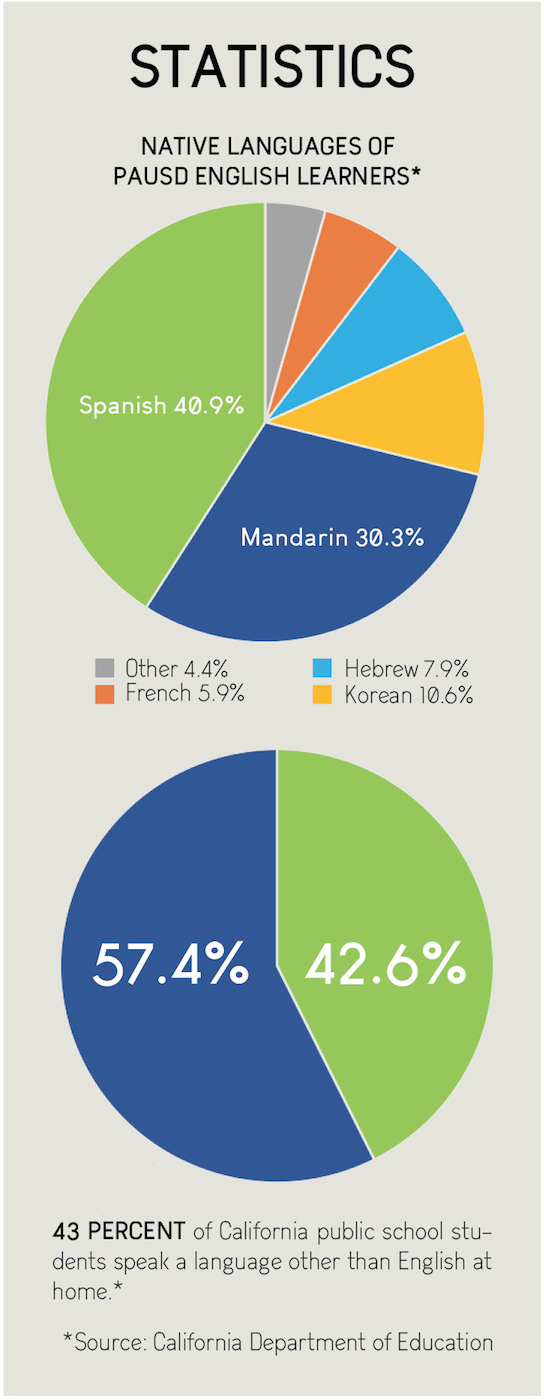

In fact, 42.6% of California public school students speak a language other than English at home, according to the California Department of Education.

The Palo Alto Unified School District has even made efforts to educate younger students in world languages, with the 10th anniversary of Ohlone Elementary School’s Mandarin Immersion Program next fall.

But does fluently speaking two languages give students an advantage?

According to Kenji Hakuta, an expert on bilingual education and professor emeritus at Stanford University, it can be difficult to determine if bilingual students actually learn better than their monolingual peers.

California students who started off as English learners and later became proficient show higher state standardized test scores than the average student of English-speaking background. However, Hakuta cautions that this is only a correlation, and does not necessarily indicate that bilingualism makes students better at learning other subjects.

Beyond school, bilingualism has been shown to reduce the risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s later in life.

For bilinguals, the onset of dementia is delayed four years compared to their monolingual counterparts, according to a study by Ellen Bialystok comparing the medical records of bilingual and monolingual patients at a memory clinic in Toronto.

Studies indicate that bilinguals learn a third language more quickly than monolinguals learning a first language. However, these studies lack statistical rigor because it is impossible for researchers to randomly assign a subject to be bilingual.

Carla Guerard, Paly French teacher and World Languages Department instructional leader, agrees that students learn a third language more easily than a second language.

“They [students] use the basis they acquired learning that second language to learn the third language,” Guerard says.

Guerard herself grew up in a household learning French, Spanish, and Italian. She later picked up English in school. At times in her life, being multilingual has made life difficult for Guerard.

“You have to remember, I had four languages in my head, so it’s a lot going on,” Guerard says.

Although starting school without knowing English may have initially delayed her education, Guerard says that overall, multilingualism has benefited her life.

Paly junior Grace Lam had a similar experience growing up in a Mandarin-speaking household. Sometimes, she thinks of an applicable idiom in one language, but cannot find a good translation. For Lam, the benefits of bilingualism are mostly cultural.

“There’s an aspect of culture that you learn, an ability to see from a different perspective, than just the all-American perspective,” Lam says. “If you understand the language, it’s easier to understand how people think.”

Guerard has similar perspective.

“Knowing more languages brings you to know more cultures and brings you to be a little more open and understanding about others’ diversity,” Guerard says.

![PARLEZ-VOUS FRANÇAIS? Juniors Grace Lam (left) and Saki Matsumoto (right) converse in French. Both students are bilingual and learning a third language. Lam grew up speaking Mandarin and Matsumoto speaks Japanese. They are now developing their linguistic skills in Advanced Placement French. “I think that it [knowing Mandarin] has given me a better ability to pick up other languages,” Lam says.](https://palyveritas.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/IMG_2921-900x601.jpg)