A Deep Look Into the Shallows

The science behind local tidal communities

Striped Shore Crabs eat everything from kelp to snails. Although they must wet their gills occasion- ally, they can stay out of the water up to 70 hours, according to Animal Diversity Web.

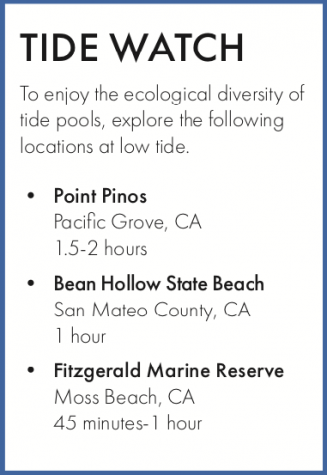

As the tide retreats and the coast returns from submergence, the abundance of marine life becomes apparent. Depressions in the rocky formations create seawater pools filled with more life than first meets the eye.

Look harder and you’ll see that these petite ecosystems teem with creatures: starfish gripping the rocks, crabs shuffling along the sand, and anemones tucked away in small cracks and crevices.

Tidal species face a multitude of environmental changes due to the ocean’s rhythmic rise and fall including long exposure to the sun and predators during low tide, harsh waves and currents during high tide, and constant fluctuations in both salinity and water temperature. During low tide, the water temperature rises and the salt content decreases.

Because tidal organisms are vulnerable at low tide, they have developed adaptations key to their survival in these two extreme water levels. To name a few, the sculpin, a common tidal fish, disguises itself changing both its pigmentation to match its surroundings, and the decorator crab attaches small organisms onto its back to blend in, according to the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Other species, however, resort to hiding under the rocks to put physical barriers between themselves and predators.

Aside from predation, organisms also face long hours of dryness at low tide. To avoid dehydration during these periods, shellfish can lock their shells closed to capture water and the ochre sea star is able to withstand longer air exposure as compared to its counterparts, according to the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums.

High tide presents a different set of challenges. Harsh waves and currents often pull unprotected animals out to sea, so many species have adaptations to ensure that they are anchored to a rock. Sea stars have hundreds of suctions on their feet to keep hold, barnacles produce a glue to bind themselves to rocks and shellfish live in large groups to reduce the force on each individual.

Aside from natural environmental stresses, climate change poses a huge threat to tide pool organisms. Increased water and air temperatures will continue to expand the volume of water, thereby shrinking coastal habitats and causing localized extinctions. For now, these pools provide a window into a miniature world.